Books

Poetry

Footnotes to the Mahabharata

New Delhi: Westland, 2025. (ISBN: 978-9360450045)

In Footnotes to the Mahabharata, K. Srilata draws readers into the inner worlds of the Mahabharata’s most feisty women – Alli, Hidimbi, Draupadi, Gandhari and Kunti. Drawing inspiration from a range of sources within the Mahabharata canon, the five poetic sequences which constitute the book are shaped around what remains unexamined or invisible within most tellings.

Read more

In Footnotes to the Mahabharata, K. Srilata draws readers into the inner worlds of the Mahabharata’s most feisty women – Alli, Hidimbi, Draupadi, Gandhari and Kunti. Drawing inspiration from a range of sources within the Mahabharata canon, the five poetic sequences which constitute the book are shaped around what remains unexamined or invisible within most tellings.

“Srilata’s polished gems illuminate the inner world of the Mahabharata, where the women live and love and wait and watch. The epic comes to us already replete with treasures and here, Srilata enriches it further with new forms and insights, new voices and perspectives.”

– Arshia Sattar (Translator, Scholar and Writer)

“In her new work, K Srilata adds her voice to the mounting cultural imperative to transform footnotes into mainstream narratives, cameos into protagonists. Shadowy female figures of the Mahabharata seize the spotlight, making sure we get their stories right this time around. The figure of Alli, in particular, lingers — a reminder perhaps that she merits her own independent volume at some point in the future.”

– Arundhathi Subramaniam (Award-winning Poet and Author)

“In Footnotes to the Mahabharata, K. Srilata draws readers into the inner, intimate, worlds of some of the Mahabharata’s most compelling women whose choices and destinies power the narrative even in the canonical tellings, although they are usually denied the space there to express themselves. Through sections that thrum with the warm, confiding tone of Sangam-era poems, K. Srilata brings these protagonists to vibrant life, collapsing the distance between their mythical travails and desires, and our current-day ones. Footnotes to the Mahabharata is a reminder that the wisdom, the timelessness of foundational epics lie not in their size, but in the capacity to explore and bare the crevices of the soul.”

– Karthika Nair (Poet, fabulist and librettist)

Excerpts

From the Hidimbi sequence:

They Say

that I give off a certain animal smell,

that I am too much, too loud,

too dark, too muscular,

too wanton,

that I am a sorceress and a thief,

that if only I had thought to look in the mirror,

I wouldn’t have dreamt of a Kshatriya man,

that a Rakshasi like me should know better,

that good men should guard themselves

against creatures like me,

that trapped by the likes of us,

they lose themselves.

palash flowers —

biting my lips

until they turn red

Fiction

Table for Four

New Delhi: Penguin, India, 2011(ISBN: 978-0143068198)

Table for Four, a novel long-listed for the Man Asian Literary Prize 2009, is a mysterious and compelling story of three graduate students and their quirky landlord. The novel is a reflection on the burden of secrets, the pain of remembering, and the betrayals, loss, and tragedies of our lives.

Read more

It is their last evening together. Maya, Sandra and Derek, graduate students at UC Santa Cruz, and house-mates for three years, prepare to sit down at the tortoise listening table for dinner with Uncle Prithvi, the house-owner. It’s a cheerful and quirky household: Sandra is prone to ‘Orkut attacks’; Derek silently pines for a wistful-looking Afghan boy in a photo he took as a war-journalist in Afghanistan; Maya, who has a crush on Derek, is inexplicably terrified of the ocean; the elusive Uncle Prithvi communicates through notes he leaves all over the place.

Sad at parting, perhaps forever, and half tipsy, they play a game of telling stories—their own stories. As the evening deepens, unexpected secrets, fears and sides of the four lives are unveiled. Sandra, abandoned at birth, tells of growing up in an orphanage with her precious disabled twin Solina, only to be separated by circumstances; Uncle Prithvi rues the loss of his beloved daughter, whom he betrayed when he sought a new life with Karen in the US. And Maya and the suddenly-absent Derek cannot bring themselves to voice their tragedies—except via soliloquy.

Mysterious and compelling, Table for Four, long-listed for the Man Asian Literary Prize 2009, is a rumination on miniature ivory of the burden of secrets and the pain of remembering and accepting the betrayals, loss, and tragedies of our lives.

Excerpts

Chapter One: More than Just Pickle and Bread

I had this strange sense of dressing for a performance, this Micawberish feeling that something was bound to turn up. Rummaging inside my suitcase for my indigo blue salwar kurta – the only Indian outfit I had carried with me to Santa Cruz, I wondered why Prithvi uncle had chosen to emerge from his seclusion. Why had he called us to dinner?

I felt a bit strange in the kurta, having never worn it in my three years here. Santa Cruz was a small, earthquake-prone town, very white-hippie. A town I couldn’t read at first. And so, with the caution of most strangers, I had chosen to blend in, never venturing beyond jeans and T-shirts.

When I emerged from my room, I very nearly collided with Sandra. She had on a short black skirt and a pink top. Sandra carried herself well in Western formals, partly because she didn’t have an ounce of extra flesh and partly, I supposed, because she had grown up wearing them. She also nearly always wore make up. Today it was pink lipstick and eye shadow. The Barbie look. A pair of hematite earrings dangled saucily from her ears. Her hair was freshly washed.

“Wonder where Derek is,” I said.

Sandra pointed to the bottle of wine that rested on the kitchen counter. “Must be getting dressed,” she winked.

Of Prithvi uncle too, there was no sign, though the kitchen smelt reassuringly of masala and I caught a whiff of something that I thought was biriyani. For the first time in the three years I had lived there, the kitchen smelt neither of Mexico nor of Kamalakka’s remembered recipes.

Suddenly, the front door opened and Prithvi uncle entered looking like a wizard. He was wearing a somewhat faded ikkat kurta over his trousers. His face was marked by a great stillness, of a patient waiting.

Prithvi uncle gestured in the direction of the circular dining table.

“Please,” he said. “There’s more than just pickle and bread,” his eyes glinted.

The expression he had worn on coming in had vanished without a trace. Sandra and I exchanged guilty looks. Had he overheard us discussing his eating habits?

Chapter Two: Tortoise Table

He had always been a bit of a recluse. Kept to himself most of the time. Sandra, Derek and I saw little of him during the day. Sometimes we wondered if he had left that house with its neglected garden altogether. But every now and then there would be some small sign to say Prithvi uncle was still around – an unwashed plate in the sink that was not mine or Sandra’s or Derek’s, kitchen lights that Sandra swore came on sometimes in the wee hours of the morning, crumbs under the table that were not our doing, a new bottle of gonghura pickle, a copy of Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile with his name on it that Derek found on the living room sofa and yes, those post-it notes on the fridge.

In all my three years at Number 14, Bay Street, I met Prithvi uncle exactly four times.

The first time was when I went to check out the house. I had been haunting the UC Santa Cruz Campus Housing office for weeks. The woman there must have been sick of me. Her good mornings had certainly gotten feebler. But I had had little luck with my apartment hunt. Either the rent was way too high or the place too far from campus. I was just beginning to wonder if this business would ever end when that hand-written poster appeared on the Housing office bulletin board.

Nice room with a view of the outside. No fuss landlord. Minimum interference. Rent $250.

14, Bay Street, Santa Cruz.

Phone Prithvi at 831-420-5130

My eyes popped. At the $250 (which was really nothing at all for a room in that neighbourhood) and at the name Prithvi – for it sounded Indian. There were so few Indians in Santa Cruz. I was curious. Was he Indian Indian like me? Or Indian born and raised in America? I phoned the number mentioned in the advertisement, wondering all the while what the catch was. A voice at the other end answered, “Good Evening, Prithvi here,” in an accent that was most definitely urban Indian, though it carried traces of some years spent in America. He proceeded to give me directions over the phone in a slow, careful sort of way. “Remember, corner house, Bay Street, opposite the pond,” he said finally, “You can come this evening. You aren’t doing anything else anyway. Come and check out the place.” It was only after I had hung up that the oddity of what he had said hit me. You aren’t doing anything else anyway. How the hell would he know that? Or was he just being presumptuous? It hit me too that he had asked me nothing about myself.

Poetry

Three Women in a Single Room House

New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2023. (ISBN: 978-9355486264)

A memoir in poetry, Srilata’s collection Three Women in a Single-Room House, traces the bitter-sweet shape of family and female lineage. Every area of human life becomes the subject of the poet’s empathetic gaze – from a child whose grandmother sews her a dress two sizes too large, to a young woman with autism proudly declaring that she is married to marbles buried in the playground of a school that has been turned into a temporary vaccination camp during covid.

Read more

A memoir in poetry, Srilata’s collection Three Women in a Single-Room House, traces the bitter-sweet shape of family and female lineage. Every area of human life becomes the subject of the poet’s empathetic gaze – from a child whose grandmother sews her a dress two sizes too large, to a young woman with autism proudly declaring that she is married, to marbles buried in the playground of a school that has been turned into a temporary vaccination camp during covid. A rich collage of experience, Srilata’s poems are intimate and heart-warming, luminous manuals for living.

“There are many ways to respond to ‘the long slow burn’ of relationships. K Srilata’s poems are poignant because they never choose to make heavy weather of it. Instead, they search for ways to take up space in single-room homes, make their peace with the prohibited box in the loft, snipped family photographs and unseen ‘ghutan’. These poems live out the daily heartache of being human with tender understatement and a characteristic lightness of touch. And yet, the unbandaged burn makes for a more unbandaged form, allowing for a growing suppleness of line and freedom of tone.”

– Arundhathi Subramaniam, Poet, Author, Poetry Editor and Arts Critic.

“How to reach a proper grieving, a laying to rest? Good poetry focuses on asking the right questions. Great poetry acknowledges there is rarely an answer. In K Srilata’s ‘Three Women in a Single-Room House’, there is much to be laid to rest: an absent father, three generations of women who grew used to small spaces, a beloved daughter’s origins lost in the mists of time, the role of redundant mother, the shock of middle age against the backdrop of a global pandemic. The strength of this powerful collection lies in each poem honouring the complexity of the question, giving each loss space to be felt and acknowledged. Poem by poem, the poet builds room after room, where loss can breathe, the sky can float through the slats, the past can lay its head, and the present opens each door wide.”

– Anne Tannam, Poet in Residence at Poetry Ireland (2023-2025)

“K Srilata’s new collection of poems is animated by the courage, the resilience, and the tragic yet unbowed wisdom of women – individuals who have had to resist the unforgiving pressures of a patriarchal, hierarchical society, and to flourish despite the constraints such a society seeks to impose on the female subjectivity. Srilata’s life circumstances have situated her in a matrilineal genealogy. This has been a source of strength and inspiration. Family, in Srilata’s Three Women in a Single-Room House, is at once a fragile construct and a resolute commitment, a web of relationships that can fail sadly despite intimate blood ties yet prosper beautifully without genetic connection…

Compression and expansion, inhalation and exhalation – these poems convey the many moods and occasions of breath, the breath that gives us life and that we form into expression; and which is also the token of our profound vulnerability. As memoir, as elegy, as prayer, as hymn, these poems mark yet another milestone on the journey of a very fine poet who, in her pensive quietude, claims our complete attention.”

– Ranjit Hoskote, Indian poet, art critic, cultural theorist and curator.

Excerpts

Three Women in a Single-Room House

I

Not-too-small, not-too-big,

this apartment with its balcony

on which our son can ride his tricycle,

its kitchen with no walls

so we can cook and still belong

to the rest of the house

is what I have sold my diamonds for –

thinking over the agent’s glibness

of my grandmother

who had bequeathed them to me.

They had once shone,

talisman-like, in the dark of that small room

where we three lay – she, my mother and I –

on the floor in a row,

three women used to small spaces.

II

My mother is sitting on the only bed

in the only room in the house

writing something.

When she is done,

I find an ink stain on the sheets.

One of them is an outstretched wing.

III

My grandmother is working her sewing machine

in a corner of the only room in the house.

She is making me a dress two sizes too large,

so you can grow into it, she says,

and when it is done,

go on, try it.

IV

It was never more than seven steps

from anywhere to the only window

in the single room house

and I would like to tell you

that the sky floated in through the slats,

filled us – my grandmother, my mother and I –

with spaciousness.

I would like to tell you

that we learnt to take up space,

The truth is

we just grew used to small spaces,

the three of us,

rough diamonds stuck

in mines that ran too deep

to catch the light.

Non Fiction

This Kind of Child: The `Disability’ Story

New Delhi: Westland, 2022. (ISBN: 978-9395767521)

In This Kind of Child, Srilata brings together first-person accounts, interviews and short fiction which open up for us the experiential worlds of persons with disabilities and those who love them. The book offers a multi-perspectival understanding of the disability experience—its emotional as well as imagined truth, both to the disabled themselves as well as to those closely associated with them.

Read more

‘I am the mother of a child who did not fit the school system, a child who was disabled by it.

She was a child who made “errors”, “mistakes” that the school system was unforgiving of.

We were told by the principal of an alternative school that they could not possibly admit “this kind of child”. My daughter went from being a child to “this kind of child” in that one moment.’

When she started working on the book, it was Srilata’s daughter who was its protagonist. But soon, she realized that there was no way she could stop with her daughter’s story. With each step ahead (or back), she became acutely aware of the larger story of the things we frame as ‘disability’.

‘I have learnt that disability is profoundly political, that it is heartbreakingly social.’

In This Kind of Child, Srilata brings together first-person accounts, interviews and short fiction which open up for us the experiential worlds of persons with disabilities and those who love them. The book offers a multi-perspectival understanding of the disability experience—its emotional as well as imagined truth, both to the disabled themselves as well as to those closely associated with them.

‘I have learnt that stories are always bigger than they seem at first—bigger, wider and deeper.’

At the heart of this book is inter-being and the question: What does it mean to love and accept yourself or someone else fully?

Excerpts

Introduction

Towards an Understanding of the ‘Disability’ Story

There is an old Buddhist story with resonances for the disability story we are about to embark on. When Kisa Gautami, the wife of a wealthy man of Shravasti, the capital of Kosala, loses her only son, she is overcome by a great sorrow and nearly loses her mind. Following the advice of an old man, she meets the Buddha, who tells her: ‘I can revive your child on one condition. Bring me four or five mustard seeds from any family in which there has never been a death.’ Gautami sets out to do his bidding, wandering desperately from house to house—only to find that there isn’t a single one which has not experienced death. This, to her, is a profound lesson on mortality, the fact that death is everywhere.

To look for a body that has never experienced disability, or for people who have never been touched by the disability experience, is akin to Kisa Gautami’s search for a family that had never suffered death. Chances are that we all know someone who has a disability. This person may have a disability from birth, may have acquired a disability later due to an illness or accident, or thanks to the ubiquitous process of ageing. This disability may be visible and obvious, or not. Our own bodies may have become, at various points, the sites of a disability—due either to the natural process of ageing or an accident. There is another issue we might want to keep in mind when it comes to thinking about people with disabilities. Sometimes, we hear that someone has ‘outgrown’, ‘overcome’ or ‘compensated for’ a disability. But for every such ‘positive’ account, there are also people who can’t or don’t ‘outgrow’ or ‘overcome’ their disabilities. Given our culture’s preference for ‘success’ stories, the only people with disabilities we want to hear about or hear from are the ones who have ‘made it’ in some way. The narrative of overcoming is, of course, a powerful one, and not to be discounted. However, this should not be the only narrative we pay heed to. What we should be asking ourselves is: What of the ‘non-successes’? What of their lives? What are the cracks through which they have fallen? How have they been failed? What value do their lives hold inherently? What of the lives of those who live with disabling pain that prevents them from leading a full life?

Poetry

The Unmistakable Presence of Absent Humans

Mumbai: Poetrywala, 2018. (ISBN:

978-9382749943)

The poems in this collection reflect on ideas of loss and absences, moving beyond the personal where the absence of someone important becomes a profound presence into larger issues of people in conflict-ridden zones, of people who are made to disappear.

Read more

“In a world of loss and absences, K. Srilata’s concerns go beyond the personal into larger issues of disappearing languages and people in conflict-ridden zones. Her sensitive eye for detail, the unexpected images and her use of language that can be both sharp and delicate, make these poems memorable. Her mastery of craft strengthens both her shorter poems, which rest on a single image and her longer ones where line lengths mirror the waves. This is a collection of poems to savour, full of deep thought and emotion.”

—Menka Shivdasani, Indian poet

I love Srilata’s book, her light touch, her true poetic-voice, and her ability to catch a poem on the wing and transmit it to her willing and excited reader. I wish her all the best with this gorgeous book.

—C. Murray, Poet and editor of Poethead

The poems in this beautiful and honest collection are written using language that seeks less to impress, and more to impress upon. Themes that at first appear diametrically opposed: absence and presence, freedom and restriction, loss and fulfillment, the deeply personal and the deeply political, through the poet’s assured and thoughtful handling, merge to reveal a rounded life, fully lived. The poems show that the very restraints we believe tie us down can also be wings offering us the sky. K Srilata, in writing this important collection, has given voice to all who struggle to find meaning, who wonder endlessly what that other reality might be – the one that lies just beyond our reach, just beyond the picture frame. Her writing invites us to see the unanswered questions as doorways back into our lives, opening us up to look beyond the awful permanent fright of being and see a million other beautiful things.

—Anne Tannam, Irish poet and facilitator of the Dublin Writers’ Forum

Excerpts

It is 1966

I am not born.

My father knocks on the door of a house

I have never seen.

There at the door, stands

my mother, slender,

a sprig of jasmine in her hair.

I take a taxi to the park

where they are sitting on a bench,

a foot apart from each other,

he with his face resolutely averted,

she with her eyes on the poorly tended flowers.

It’s the beginning, I know, of that great quarrel.

My mother no longer a new bride,

the edge of her sari already a grieving afterthought.

She doesn’t see me.

She sees only the crumble of her years.

I am to hold forever the grating harshness of it all.

I walk up, older, already, than them both,

tell them I am their only daughter—

and will they please please look at each other

the way they had the day he had knocked on the door

and she had let him in,

jasmine in her hair.

My mother looks at the flowers, the crumble of her years.

My father, away, from us both.

(after Agha Shahid Ali’s “A Lost memory of Delhi”)

Translation

The Rapids of a Great River: The Penguin Book of Tamil Poetry

(co-edited with Lakshmi Holmstrom and Subashree Krishnaswamy)

New Delhi: Penguin India, 2009. (ISBN: 978-0670082810)

Hailed as a landmark collection of Tamil poetry in translation, The Rapids of a Great River traverses the Sangam and bhakti periods, moves on to pre-modern poems from the nineteenth century and closes with a compilation of modern and contemporary poetry. Breaking free from prescriptions, the new voices represented here include Sri Lankan Tamils, women and radial dalit poets, among others.

Read more

The Rapids of a Great River begins with selections from the earliest known Tamil poetry dating from the second century CE. The writings of the Sangam period laid the foundation for the Tamil poetic tradition, and they continue to underlie and inform the works of Tamil poets even today. The first part of this anthology traverses the Sangam and bhakti periods and closes with pre-modern poems from the nineteenth century. The second part, a compilation of modern and contemporary poetry, opens with the work of the revolutionary poet Subramania Bharati. Breaking free from prescriptions, the new voices—which include Sri Lankan Tamils, women and dalits, among others—address the contemporary reader; the poems, underscored by a sharp rhetorical edge, grapple with the complexities of the modern political and social world.

The selection is wide-ranging and the translations admirably echo the music, pace and resonance of the poems. This anthology links the old with the new, cementing the continuity of a richly textured tradition. There is something in the collection for every reader and each will make his or her own connections—at times startling, at other times familiar.

Excerpts

Banyan

—R Vatsala

(Translated from the Tamil “Aalamaram”)

I am a banyan.

No, don’t laugh.

Indeed, I am a banyan.

Though I fit snugly into this tiny pot,

a banyan I am.

Much like that giant tree,

I am,

a million leaves

quivering,

mocking,

spitting rotten fruit.

Trust me,

I too am a banyan.

me, with my less- than-hundred leaves.

Like that monster

with deep roots

which can uproot me from home,

I too am a banyan.

Truly,

me with roots like nerves.

Trapped in a pot,

roots clipped,

branches broken,

I’ve no choice

but to be a dwarf.

Me, who stands in the shade

of this great tree.

It is my tiny figure that charms.

I am a crowd puller.

A little girl asks,

“Why didn’t they plant this tree on earth?”

Bang comes the reply:

“It is not big enough

to survive on the ground.”

The little girl claps her hands and laughs,

“Only if you place it on earth, it can grow, no?”

I shake my leaves

and bless her.

Child, may you grow to be a banyan tree!

Translation

The Scent of Happiness

(translated from a Tamil novel by R. Vatsala)

New Delhi: Ratna Sagar, 2021. (ISBN: 978-8194756095)

R. Vatsala’s novel The Scent of Happiness (Ratna Books, 2021) is a feminist bildungsroman, one that focuses on the psychological and moral growth of its female protagonist. It offers a sharp critique of gender politics as it plays out both in the private, familial sphere as well as in the public sphere, the world of work. The story of its protagonist Prema is the story of thousands of women of her generation, women who grew up in the heady years immediately following the formation of an independent Indian nation state. Vatsala’s novel is a survivor’s story, the story of all women who survive domestic abuse and navigate stone-walling at the workplace

Read more

R. Vatsala’s novel The Scent of Happiness (Ratna Books, 2021), translated from the Tamil original by K. Srilata and Kaamya Sharma, is a feminist bildungsroman, one that focuses on the psychological and moral growth of its female protagonist. It offers a sharp critique of gender politics as it plays out both in the private, familial sphere as well as in the public sphere, the world of work. The story of its protagonist Prema is the story of thousands of women of her generation, women who grew up in the heady years immediately following the formation of an independent Indian nation state. The Scent of Happiness foregrounds the idea of freedom, both personal and political. Ironically, India’s newly acquired political freedom means little to the lives of women such as Prema who are raised for marriage and domesticity, their lives tied to patriarchal strictures at every step. And yet, survive they do and how. Vatsala’s novel is a survivor’s story, the story of all women who survive domestic abuse and navigate stone-walling at the workplace.

Excerpts

The new house was very far from Prema’s school. In those days, Jamnagar had only a skeletal bus service. So Prema had to walk the entire distance…

It was only Amma who lamented constantly, “How thin she has grown thanks to walking so far every day! What is she going to achieve studying so hard, that too in Gujarati?” To this, Appa said, “I too used to walk from my village to town to reach school when I was young. It is good to walk. Walking increases your appetite. She will eat well.”

But this did not happen. The walk to and from school left the already weak and delicate Prema exhausted. When she got home, she had no energy to do her homework properly. She wasn’t able to complete her lessons and struggled to keep pace with what was being taught. Since all the lessons were taught in a language she was only beginning to understand, she needed to put in a lot of hard work in order to comprehend her lessons properly. This was something she could not manage. Her lessons remained unlearnt. All along, she had believed only that she was not as intelligent as her brother. But now she began to suspect that she was completely stupid.

Two months had passed since they had moved house. One day, Prema came down with a fever. Her body ached all over. She found it difficult even to get up from bed. “All this is only because she walks so far every day,” declared Amma. The fever abated after five days. But the body ache took a week to go away. The temperature reading on the thermometer adamantly refused to go down from ninety-nine degrees. “You can’t really call this kind of thing a fever,” the doctor laughed, “It will go away on its own.” And then, glancing at Prema he asked, “Taṉē skool sārum nati lagtun. Yēj nē? You don’t like school, isn’t that so?” Prema was at a loss for words. Appa said, “Let her start going to school from tomorrow.” Amma said, “What does this Gujarati doctor know about her health? She has always been weak. What will we do if she faints and falls down while walking all the way in her feverish state? We won’t even get to know.” Appa kept silent. Amma checked her temperature every day. Studying the thermometer with her lips pursed, she would say, “It’s still the same.”

Prema grew tired of lying in bed. She ventured out into the garden to play. After some days, Amma stopped sticking the thermometer under her tongue. For Appa, it was a busy time at work. That entire month, he did not get home before dark. Even on the weekends, his work consumed him. After everything was over, he asked, “What happened? She has recovered now, hasn’t she? Shouldn’t we send her to school?” Amma said, “She has been weak since her childhood. Things have become worse now. Look how thin she is! If we send her back to school, she may fall ill again. Moreover, how will she make up for all the lessons she has missed so far? Forget it. She is a girl child. Very ordinary looking. Who will marry her tomorrow if she is as thin as a stick?” Appa kept mum. Prema’s education came to a halt with fourth grade.

Translation

Once There was a girl

(translation of the Tamil novel Vattathul by R.Vatsala)

Kolkata: Writers Workshop, 2012. (ISBN: 978-9350450277)

The winner of the Tiruppur Tamil Sangam award for Best Novel, 2008, Once There Was a Girl is a poignantly narrated novel about Rani alias Janaki, a feisty young woman who is married off to a childless widower from a conservative Thanjavur Brahmin family. Rani has to negotiate and survive the complex familial politics that threaten to engulf her life, while her daughter Prema who lives through a painful divorce, has to bear the brunt of Janaki’s limited way of imagining women’s lives.

Read more

The winner of the Tiruppur Tamil Sangam award for Best Novel, 2008, Once There Was a Girl (translated by K Srilata) examines the way women are perceived in contexts which are inherently patriarchal. Spanning the entire twentieth century from pre to post-independence India, the novel is a poignantly narrated tale about Rani alias Janaki, a young Brahmin girl with spunk, attitude and native intelligence. Married off to Raghuraman, a childless widower from a conservative Thanjavur Brahmin family, Rani has to negotiate and survive the complex familial politics that threaten to engulf her life. If Janaki’s wings are clipped by the patriarchal culture of the mid-twentieth century, it is not without consequence. Her daughter Prema, who lives through a painful divorce, has to bear the brunt of Janaki’s limited way of imagining women’s lives. And yet, Janaki endears herself to us.

A feminist bildungsroman, Once There Was a Girl is rich in period-detail. Both linguistically and culturally, the novel affords us a unique insight into the mindscapes of women who lived through times radically different from our own.

Excerpts

Chapter 1

It struck her suddenly that it was going to be a full moon night. The pournami after this one would be the festival of avani avittam and her birthday as well. She felt burdened by the thought. As the morning breeze grazed her skin, she shivered slightly.

She isn’t able to take the cold these days. In the old days, she would wake up at the crack of dawn and bathe before she entered the kitchen… She would be done by eight. But all that has changed of late, ever since she moved in here, in fact. These days, she has to literally drag herself out of bed. She doesn’t want to bathe. Can’t stand the thought of cooking or eating. And yet, there seems no way out of this quagmire. She has had to push herself to cook. There was a time when she used to bathe twice a day. Now one bath is all she can manage. She can’t be bothered doing her hair. She is so tired… She can’t go on like this…

At sixty eight, her body is still strong. It is a body used to labour. From the time she got married – she was fourteen when she entered her husband’s home – she has toiled. But she can no longer keep it up. Twenty days ago the old man took to his bed. Feeding him on time, keeping him clean, turning him over every hour so the bed sores don’t set in… no, there is no way she can do it all. She wishes him dead. Yearns for a few years of freedom. Freedom from the old man’s nagging. Then she can cook when she feels like it, survive on curd rice when she is not in the mood for anything more elaborate … It is not as if she can rely on Narayanan after the old man’s passing. But all that no longer matters. Her stomach burns when she thinks of Narayanan. How much love she had poured into that boy of hers! So? That no-good wife of his had gone and abandoned him. Now what was she to do about that? He hates her so! Let that be. He will get what is coming to him. Speaking to his own mother like that! Why! She had given him life! He was headed for disaster. Her heart skips a beat. How can she curse her own son like this? And then again, why ever not? Is it right for him to behave like that? Her eyes fill up. It was all that witch’s doing. It was she who had turned her son against her. He had been such an affectionate son before. The witch had poisoned his mind. Her face flushes with anger. At that moment, she could have killed her daughter-in-law…

Forcing herself to rise from bed, she brought the milk in. Once the milk was on the stove, she brushed her teeth and made herself some coffee. She felt some of her energy return. She got the old man to sit up and helped him brush his teeth. This done, she served him his coffee, helped him back into bed and headed for the bath. Once again, the same, familiar fatigue hit her. She got the rice going and prepared the ragi kanji. It was the maid’s day off. As Janaki started doing the dishes, her body cried out for rest. She unrolled the mat, placed a pillow on it, protecting it with a towel so the oil from her hair would not seep through and leave an unsightly stain. As she lay down, she wondered why she was so tired.

After a while, she sat up to flip through a photo album. She does this often these days. Appa’s photograph – what a handsome, dignified man! Oh, Appa! Why did you fritter away your money like that? That is why you were forced to marry me off to this man, weren’t you?

A picture of herself when she was twelve. Her father standing beside her, looking stately with his Zari turban. Her mother wearing that foolish expression. Maragatham, Rajamani and Krishnan – they were in that picture too. And she herself, holding the baby Pacha. What a beauty she was! Of what use was all that beauty though? That parrot-green coloured silk pavadai, her favorite. Appa had got it woven in Kanchipuram, specially for her. Whatever had become of it? Atthai must have flicked it, given it off to her daughter. Or, perhaps, some relation of amma’s had flattered her and the latter, seduced, must have given it away to the woman. How stupid amma was! But all that had changed! With Chanakya-like cunning, amma had managed to secure her own life. No matter that her daughter-in-law’s life had been ruined in the process. If she, Janaki, had not given refuge to her mother and brothers at the time, they would have been on the streets. Today they were doing well for themselves. It was she who had lost out. They didn’t need her any more.

Translation

i, Salma: Selected Poems

(translated from the Tamil by K Srilata and Shobhana Kumar)

New Delhi: Red River, 2023. (ISBN: 9392494572)

Salma (RAJATHI SAMSUDEEN) is a well-known Tamil writer who overcame orthodoxy to become an important political and literary voice. In this anthology, Srilata and Shobhana have translated some of her best known poems into English, preserving the fearless and bold spirit of the original.

Read more

Salma (RAJATHI SAMSUDEEN) is a well known Tamil writer who overcame orthodoxy to become an important political and literary voice. In this anthology, Srilata and Shobhana have translated some of her best known poems into English.

“i, Salma unveils scintillating poems that throb with the fervour of the original even in translation! Fearless and bold, direct and simple, these poems are rooted in the very living of life while they transform the mundane into magical and the real into surreal.”

— Sukrita Paul Kumar

Excerpts

Story of the Deep Night

(Irandam Jaamathin Kadhai)

Salma

These nights,

following the birth of my children,

you seek,

in the midst of my nakedness

so familiar to you,

an old, unblemished beauty

and are disappointed.

You are revolted, you declare,

by my fat body,

and its stretch marks.

Your own body, you say,

is unchanging.

Buried in the deep valley of silence,

my voice moans and sighs.

It’s true that your body

is unlike mine.

Loud and open,

yours proclaims itself,

Before this perhaps,

you have had children

elsewhere

and by others.

Since you have remained

unmarked by their birth,

you can be proud.

But what of me?

These birth marks cannot be mended,

neither my decay.

After all, this body is not a piece of paper

to be cut and pasted.

There is no restoring it.

Nature plays false,

much more than you.

Wasn’t it with you that it began –

that first stage of my downfall?

Stranger than evening is night,

that breeder of dreams.

The tiger,

so peaceful in the picture

that hangs on the wall,

visits my bedside at night,

watches keenly.

(Translated from the Tamil by K Srilata and Shobhana Kumar)

Non Fiction

Lifescapes: Interviews with Contemporary Women Writers from Tamilnadu

(K Srilata and Swarnalatha Rangarajan)

New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2019. (ISBN: 978-9385606199)

This unique anthology is a collection of in-depth interviews and conversations with seventeen contemporary women Tamil writers including Bama, Salma, Sukirtharani and Vatsala whose works explore what it means to be a woman writer. Each conversation is preceded by a translation from the writer’s oeuvre.

Read more

This unique anthology is a collection of in-depth interviews and conversations with seventeen contemporary women Tamil writers including Bama, Salma, Sukirtharani and Vatsala whose works explore the implications of being female in Tamil Nadu today. Each conversation is preceded by a translation from the writer’s oeuvre. The book is an attempt to understand the context and the lived experience of contemporary women writers from Tamilnadu.

Excerpts

Conversation with Bama:

Finding Reasons to Laugh

Srilata and Swarnalatha:

We have learnt much about your life from your two books,

Karukku and Sangati, which offer moving vignettes about your life in the convent, your struggles on leaving it and your persistent attempts to shrug off the shadow of caste that follows you wherever you go. Your writing has triggered a wave of social awareness and empathy in students and young people who can access it through translations and are able to understand a Dalit perspective. We think your storytelling has a very natural quality. Is this talent an innate ability? When did you decide to transmute your life experiences into the written form?

Bama: To answer your first question, I should say that storytelling is our culture. We grow up listening to stories, begin listening to them perhaps right from birth. When I was a child, my grandmother and mother used to tell me a lot of stories. There were many others.

The school was an important source of stories—our curriculum consisted of a lot of stories, unlike today’s education that attaches importance only to rigorous academic training. To elaborate, we had few or no books, we used to carry only a writing slate and maybe a few vaipadu1 books to help us memorise multiplication tables and the like. The important things were stories!

I attended school in my village, Pudupatti. If the school gave me stories, the religious context of my background also provided rich stories, from the Bible. In short, we were surrounded by stories, there were stories wherever we turned. That’s how we grew up. And so I think our culture is a storytelling culture. It may not be written but surely it is oral. As we had grown up listening to stories they inevitably took root, and when we became adults they enabled us to become storytellers ourselves. People from my grandmother’s generation were so good at it that they invented stories! We came to know more about the Ramayana and Mahabharata through the stories they shared with us, than from our school books. There was a plenitude of stories in our growing years. Thinking back, I feel that these stories had sustained, strengthened, and cheered me during those spells of pain, agony I experienced, the hard labour, poverty and other challenges.

To answer the question of how I came to write, I must point out that I didn’t start writing under pressure or because I was forced As you know, I had left the convent in1991. This was a painful moment for me. As a sixty year old woman, I’ve come across many difficulties, but leaving the convent was one of the darkest moments in my life. I had left my job as a teacher to join the convent and when I left the convent, I was economically vulnerable. I experienced psychological difficulties, too. When I was going in, leaving the outside world behind was so difficult because everything was unfamiliar. When I left the convent after seven years, leaving the convent was difficult because I was going out into a world that had now become unfamiliar to me…

It was Fr. Mark, a Jesuit priest from my village and my brother’s friend, who got me my first job. When I shared the difficulties of my life with him, tears would always come to my eyes. He suggested that I write all my feelings down in a notebook as a way of liberating myself from the burdens of my heart. He too was very busy and didn’t have much time to listen patiently to my problems. For nearly six months, I kept up the practice of writing everything down in a notebook. Writing resulted in mixed feelings, because there were teary moments when I recalled the pleasures and fun times of childhood that could never be relived. Those six months saw periods of frenetic, engaged writing as well as times when my creativity slackened.

Non Fiction

Short Fiction from South India

(co-edited with Subashree Krishnaswamy)

New Delhi: OUP, 2008. (ISBN: 978-0195692464)

A reader for students of literature, Short Fiction from South India brings together English translations of twelve short stories originally written in Kannada, Malayalam, Tamil, and Telugu. While the introduction sketches the phenomenon and history of translation in the Indian context, the exercises at the end of each unit encourage students to concentrate on various elements that constitute a story-theme, imagery, vocabulary, and style. Each story is accompanied by a short biographical note on the author, the first page of the story from the source language, a detailed glossary and comprehensive exercises to train students in reading and in translation.

Read more

A text for students of literature, Short Fiction from South India brings together English translations of twelve short stories originally written in Kannada, Malayalam, Tamil, and Telugu. While the introduction sketches the phenomenon and history of translation in the Indian context, the exercises at the end of each unit encourage students to concentrate on various elements that constitute a story-theme, imagery, vocabulary, and style. Each story is accompanied by a short biographical note on the author, the first page of the story from the source language, a detailed glossary and comprehensive exercises to train students in reading and in translation.

Poetry

Bookmarking the Oasis

Mumbai: Poetrywala, 2015. (ISBN: 978-9382749295)

The poems in Bookmarking the Oasis are odes to the magic of everyday life, the way light falls, a bright blue bird flying into the speaker’s house and leaving behind its bright blue on its way out. They are meditations on the importance of living in the moment, of rescuing it from one’s own self. Nuanced and delicate, they speak like miniature water colours.

Read more

“Many of the poems in K Srilata’s fourth collection of poetry, Bookmarking the Oasis, take shape on the page like creepers, deceptively slender and delicate, or like long fuses spelling the taut distance between ignition and explosion, or like sutras revealing themselves in short lines of a few words each, marking units of breath while also calibrating the pace of thought. Indeed, many of these poems resemble the bookmarks of Srilata’s title: as though, with each poem read, we were recording the stages of the journey we make with the poet into a world of carefully scaled and nuanced meditations on a precarious contemporary epoch in which, as the artist Adrian Piper puts it in the disquieting title of an ongoing body of her conceptually inflected work, “everything will be taken away”.

Srilata’s poems are a measured attempt at holding on to all that might be taken from us: the textures of everyday life, the temperatures of emotion, the architecture and topography of our neighbourhoods. The detail is vital to her proceedings: windows and the currents of light that hinge around them, the colour of a bird’s wings that remains in the mind’s eye long after the bird has flown away, the boilerplate prose of a school textbook that reveals its potential for surreal revelation under the poet’s forensic probing.

— Ranjit Hoskote Poet, Translator and Cultural Theorist

Excerpts

Looking for Light, Sunbirds

I wish I could show you, when you are lonely or in darkness, the astonishing light of your own being.

(Hafiz of Shiraz)

Looking for light,

sunbirds hop

on hopeful, spindly legs.

I am no different.

The same distaste of darkness,

and, at dusk, the same torment

of light fading.

Often, the only light to be had,

is desperate and feeble,

too deep to access,

my body, a manhole from which

I must rescue that one sweet ray

or remain, forever, bereft.

Bright Blue Bird

A bright blue bird

from a distant tree

flies into my house.

When it flies out, it leaves behind

its bright blue.

The blue hops down

becomes first one word,

and then, another,

till, finally, it assumes the face of a poem.

Before long, the floor is an upside-down blue sky

and the blue of the poem has made its way

into my ink filler,

into my notebook.

Poetry

All the Worlds Between: A Collaborative Poetry Project Between India and Ireland

(co-edited with Fiona Bolger)

New Delhi: Yoda, 2017 (ISBN: 978-9382579472)

Curated and edited by K Srilata and Fióna Bolger, this collaborative poetry project brings together poets from India, Ireland and in between. Participating poets include Adil Jussawalla, Arundhati Subramaniam, Vatsala, Sampurna Chattarji, Alvy Carragher, Shobhana Kumar, Anne Tannam. The poets looked at questions of home, belonging, identity, exclusion and homogenisation.

Read more

Curated and edited by K Srilata and Fióna Bolger, this collaborative poetry project brings together poets from India, Ireland and in between. Participating poets include Adil Jussawalla, Arundhati Subramaniam, Vatsala, Sampurna Chattarji, Alvy Carragher, Shobhana Kumar, Anne Tannam. Their writing partnerships resulted in four strands—poems as conversations, poems at angles to one another, poems which speak out of turn to other poets in the group and, not surprisingly, stories of friendship. The poets looked at questions of home, belonging, identity, exclusion and homogenisation. From conversations about shoes and what they evoke, to exchanges about parents, poems responding to the transgender experience, to inward-angled poems and even chain poems created stanza by stanza over email and WhatsApp, through all of these the poets found themselves eavesdropping on a collaborative consciousness, ears to the ground listening for the beat of life.

Excerpts

My silence is a wire-mesh, galvanised

and two taut-metres high

— Sue Butler (‘Silence’)

Anatomical Chart

The one on paper’s a road map without traffic,

but the screened one’s lively – stuff streaming

in brief shifts sometimes, but often, not,

night-long, repetitious, almost unending;

from long-lived-in clusters, imploded or scorched,

from sweet bodies of water to coasts

corrosive, sinking, to ageing vessels,

to huge expanses of water, or to shock,

unprepared for the pitch-black pitch overboard,

to be removed, if found, by a set procedure,

a clinical move.

Or to face more movement, forced marches,

druggings, to finally stand facing mesh, silent,

baffled again, having come through razors and coils

that duplicate, as if by magic, across every welcoming gate :

millions of bodies,

cells, leaving grounds once believed to be safe,

motherland – a womb perhaps? – kick-started now

to continue as long as it takes,

as long as it takes a body to know they’re for keeps,

and it can’t live without.

— Adil Jussawalla

Poetry

Writing Octopus

New Delhi: Authorspress, 2013. (ISBN: 978-8172737856)

This slim collection of poems showcases Srilata’s most recent work, many of which have appeared in journals such as Prairie Schooner, Mascara Literary Review, Kavya Bharathi, Recours au Poeme and Caravan. Resting on the central metaphor of the octopus, these poems about absence, invisibility, disability and poetics speak to the heart by way of the intellect. The poems employ a mix of carefully structured arguments and poetic strangeness to achieve their end.

Read more

This slim collection of poems showcases Srilata’s most recent work, many of which have appeared in journals such as Prairie Schooner, Mascara Literary Review, Kavya Bharathi, Recours au Poeme and Caravan. Resting on the central metaphor of the octopus, these poems about absence, invisibility, disability and poetics speak to the heart by way of the intellect. The poems employ a mix of carefully structured arguments and poetic strangeness to achieve their end.

Excerpts

A Graveyard of Faces

That morning, I woke without a face.

I had dropped it,

sleep-walking at night,

through

a forest of fallen trees.

The worms had gotten to

all but the ears.

In the shop down the road,

they had just sold the last human face.

“Sorry, madam. We are out of stock,” the salesman informed a friend,

“In any case, we only do disposables

and the lady, you say, wants a face

that will weather

the long winters of dying poems?

A more permanent sort of face, that would be then…

We don’t do those, I’m afraid.”

Eventually, I have to settle for a disposable.

A face that will not out-last

the forgetting of lines.

But it can do “sad”.

And it can do “happy”.

It can get on

better than my old face could.

On the first day of every month,

I walk to that forest of fallen trees

and bury my face

in a graveyard filled with my faces.

Carefully, I put on a new one,

pink and fresh from its plastic case and,

despite the absence of interested worms,

die again

and again

and again.

Poetry

Arriving Shortly

Kolkata: Writers Workshop, 201. (ISBN: 9789350450154)

This collection of free verse is woven around the stories of ordinary people like the Indian mother who comes to New York city, her body like a puzzle missing a piece – the many saris she has worn back home. The poems bear witness to the emotional truth of lived experience and deftly, with gentle irony, blur the lines between the personal and the political.

Read more

Excerpts

Arriving Shortly

When amma came

to New York city,

she wore unfashionably cut

salwar kurtas,

mostly in beige,

so as to blend in,

her body

a puzzle that was missing a piece –

the many sarees

she had left behind:

that peacock blue

Kanjeevaram,

that nondescript nylon in which she had raised

and survived me,

the stiff chikan saree

that had once held her up at work.

When amma came to

New York city,

an Indian friend

who swore by black

and leather,

remarked in a stage whisper,

“This is New York, you know –

not Madras.

Does she realise?”

Ten years later,

transiting through L.A airport

I find amma

all over again

in the uncles and aunties

who shuffle past the Air India counter

in their uneasily worn, unisex Bata sneakers,

suddenly brown in a white space,

louder than ever in their linguistic unease

as they look for quarters and payphones.

I catch the edge of amma’s saree

sticking out

like a malnourished fox’s tail

from underneath

some other woman’s sweater

meant really for Madras’ gentle Decembers.

Poetry

Seablue Child

Kolkata: the Brown Critique, 2002. (ISBN unavailable)

Srilata’s debut book of poems Seablue Child is a collection of free verse that includes her landmark poem“In Santa Cruz, Diagnosed Homesick” which won the First Prize in the All India Poetry Competition, 1998 organised by the British Council and the Poetry Society, India. The book also features her poem “Kamalamma” which won the Gouri Majumdar Poetry Prize, 2000.

Read more

Srilata’s debut book of poems Seablue Child is a collection of free verse that includes her landmark poem“In Santa Cruz, Diagnosed Homesick” which won the First Prize in the All India Poetry Competition, 1998 organised by the British Council and the Poetry Society, India. The book also features her poem “Kamalamma” which won the Gouri Majumdar Poetry Prize, 2000.

Excerpts

In Santa Cruz, Diagnosed Home-sick

At the gift shop by the wharf

I bought an indigo octopus

all arms…

I, a new comer to this

out-of –the-way white-hippie town

settle into the sea.

My two-month hostility melts

even as I see what divides me from home

more clearly than I did from my airless plane.

The sea know ways of connecting too,

of fluidly hugging,

in long-armed benevolence,

the puzzle-edges of vast continents.

Translation

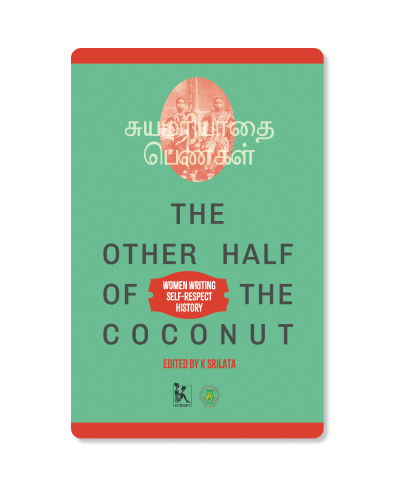

The Other Half of the Coconut: Women Writing Self-Respect History

New Delhi: Zubaan, 2002(ISBN: 978-8186706503)

Revised edition by Zubaan and the Tamilnadu Textbook Society in 2025.

In this landmark anthology of translations, Srilata trains an intersectional feminist lens on the Self-Respect movement, bringing to readers vibrant stories and essays by women self-respecters from early twentieth century Tamil Nadu. The anthology also contains translated excerpts from Moovalur Ramamrithammal’s iconic novel Dasigal Mosavalai (The Dasi’s Wicked Snares).

Read more

In this landmark anthology of translations, Srilata trains an intersectional feminist lens on the Self-Respect movement, bringing to readers vibrant stories and essays by women self-respecters from early twentieth century Tamil Nadu.

Within its pages, you meet the fiery Trichi Neelavathi urging her male comrades not to leave their wives behind at home when they attend self-respect conferences, declaring that the principles of self-respect should first touch the lives of women. You meet her again as she rails against highly ritualistic weddings and asks: “Despite the fact that the Brahmin consults the stars and performs the rituals deemed necessary for a marriage, why is it that some couples end up childless, why do some others quarrel like the mongoose and the snake?” Writer-activist Janaki offers a tongue-in-cheek listing of ridiculous superstitions such as: “If women eat alongside men, the rains will fail us! If we insist that caste differences must go, the rains will fail us!” In another essay, she writes of the petty mindedness of a temple priest who retains the bigger halves of the coconuts offered to the gods.

The anthology also contains translated excerpts from Moovalur Ramamrithammal’s iconic novel Dasigal Mosavalai (The Dasi’s Wicked Snares). Srilata argues that while the Self-Respect movement’s drive to abolish the devadasi system is central to the novel, there is a less overt textual centre—the feisty devadasi sisters Kantha and Ganavathi and their attitudes towards life.